The Demand Dilemma

Image Credits: debrief2learn via Google Images

March 28th, 2022

Matthieu Papahagi

Like inflation, employment, and other macro factors, consumer demand is best described as “important, but unknowable”, to paraphrase Warren Buffett. However, because consumer spending is so important (about 60-70% of GDP in most countries), I will still take my chance writing about it. As I believe that investing is more of a game of balance than it is of anticipation, the focus of this post is on raising some important questions and discussing how to position for a weak consumer demand environment, rather than attempting to predict exactly when, how, and by how much consumer demand will weaken. After all, even central banks have trouble doing this. This post focuses mainly on the US economy, not only due to its size and global importance, but also due to every feature of the pandemic rebound being stronger there than in other developed economies – from GDP and inflation, to Quantitative Easing (QE) and fiscal stimulus. If you are already worried about weakening consumer demand, feel free to skip my own dose of worries in the first section, and read the second section, where I discuss investment and trade ideas.

The Macro View

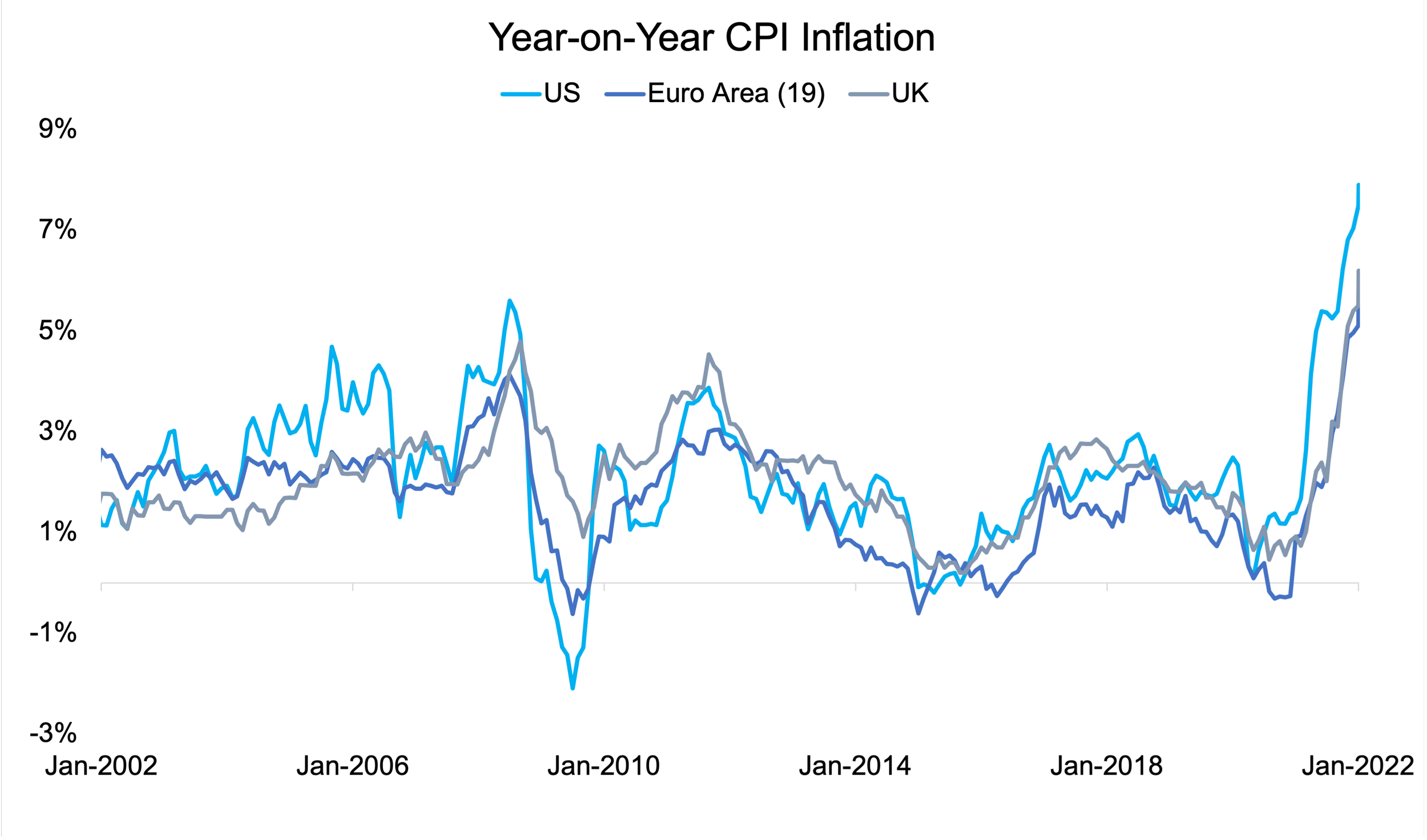

Over the past year, there has been a great deal of coverage of high inflation, which in February reached an annual rate of 7.9% in the US, 5.9% in the Eurozone, and 6.2% in the UK. This inflation was mainly attributed to supply shortages – in anything from commodities to cars and semiconductors, to housing and labour. The pandemic had disrupted production capacity globally, leading to shortages and order backlogs which in turn led to higher prices, a phenomenon only exacerbated (mainly in commodities) by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Source: FRED, The European Commission, ONS

But the other half to the story of high inflation is the strength of consumer demand, particularly in the US. This demand has been boosted by the low unemployment, strong household balance sheets, and low borrowing costs, and of course, by the easing of pandemic restrictions. What is not being discussed enough is that, unlike consumer spending, measures of consumer confidence have declined sharply since last summer – falling below the pandemic level in the case of the US and the UK. Hence, there is a “demand dilemma”: how to reconcile the strong consumer spending and the record corporate earnings with this apparently pessimistic outlook on the economy? You can read more about consumer confidence surveys here and here.

Source: OECD (Seasonally Adjusted)

Fundamentally, there are five main drivers of consumer spending – employment, wages, prices, interest rates, and consumer confidence, the latter of which can be regarded as the outlook on the other factors. I would also add a further ingredient – asset prices, especially house prices, since about 60% of the net worth of the median American family is in housing. Let’s look at each of these factors. Unemployment remains low across the board, so should not be an immediate concern, however wages look more vulnerable, since with compressed margins by high input and overhead costs, companies are likely become reluctant to keep offering higher wages. Rates, while set to rise, will still remain low for the foreseeable future, and should not have a drastic effect on consumer spending in the short term (after all, most household debt is tied in mortgages, which are fixed-rate, and so higher rates only affect new buyers). Prices and consumer confidence are the main concern – we’ve known for a while that consumer expectations for inflation have been much higher than the Fed’s expectations – the median year-ahead consumer expectation for inflation stood at 6% in February, according to data from the New York Fed, compared to a range of 2.2-3.5% for 2023 PCE inflation in the FOMC’s March Summary of Economic Projections. This pessimistic view on inflation is also reflected in the sentiment surveys, but not in spending yet – the relief from the retreat of the pandemic still dominates. One could thus dismiss these confidence numbers, concluding that prices are simply high enough to annoy people, but not high enough to destroy demand, at least in developed countries. Yet, I would argue that these numbers reflect something more profound, namely that consumers are sensing the overheating of the economy better than policymakers or market participants.

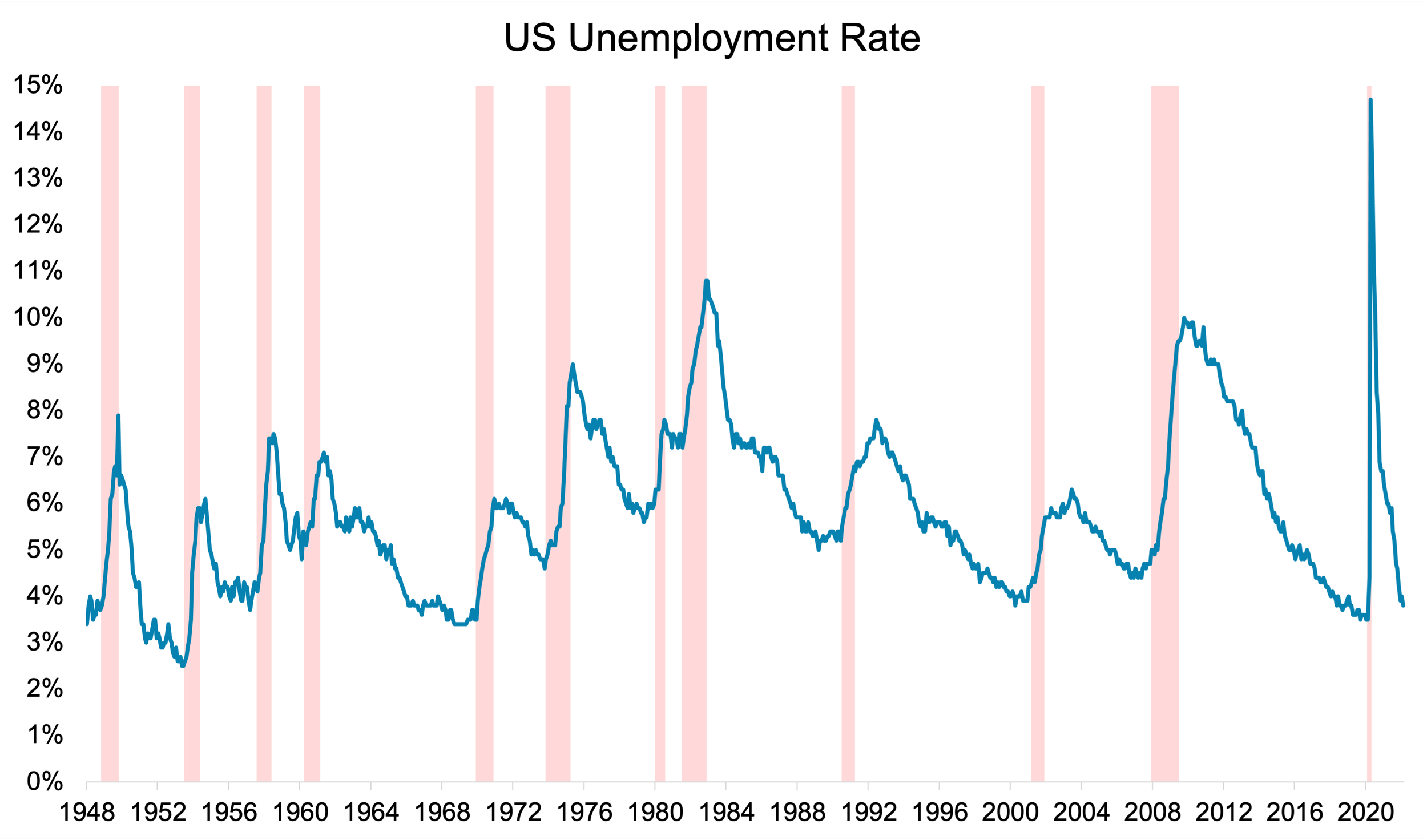

Indeed, there are valid reasons to be concerned about an economic contraction. And while some see the war in Ukraine, the high commodity prices, the plans for higher rates, and the nearly inverted 2 year - 10 year segment of the Treasury yield curve as ominous signs, I do not think that these are the most imminent threats to US and developed market growth (especially the yield curve inversion, given how QE has affected price discovery in credit markets). Rather, I believe it is the fact that the pandemic, as Ken Fisher puts it, acted not as much as a conventional economic recession and financial bear market, but more as a brief and oversized economic constriction and market correction. Take as an illustration of this the unemployment rate, which is a very good measure of market cycles, with long periods of low unemployment preceding recessions, which in turn cause high unemployment. The pandemic was more sudden and powerful, but also more short-lived, than any of the prior crises.

Source: FRED

Essentially, an economic cycle ends on broad overheating originating from an unsustainable excess in some part of the economy, such as the rampant speculation in growth stocks in the late 1990s or the housing boom amplified by unchecked financial leverage in 2005-2007. However, instead of resetting the market cycle, the huge fiscal and monetary response to the pandemic only prolonged the economic boom that started in 2009. Arguably, apart from the ever-rising debt, there weren’t any major excesses in the economy prior to March 2020 (I do not think that the above-average stock valuations are comparable to the dot-com madness). But excesses were created during the pandemic, not least due to the ramp-up in QE and fiscal spending. As Howard Marks puts it, 2020 was the year when the word “trillion” became common parlance, with over $5 trillion in fiscal spending, and about $4.7 trillion in QE in the US to date. Unlike in 2007-2008, this major injection of liquidity throughout 2020 and 2021 reached everyone’s pockets, lifting household savings and institutional portfolios alike. This sudden excess cash initially led to some asset price inflation and to strong consumer spending (particularly in goods, due to the mobility constraints of the pandemic), thus boosting corporate earnings and increasing the need (and the wages) for more labour to keep up with the demand. However, even this record spending was no match for the increase in household balance sheets, leading the personal savings rate to surge for a second time in the first quarter of 2021 (admittedly, the second wave of COVID-19 contributed to this as well). The dissipation of this off-the-charts level of savings back to a normal rate coincided with the strong rally in equities and housing in the last three quarters of 2021. However, while the savings rate has since normalised, spending remains significantly above trend. Besides amplifying the TINA (There Is No Alternative) phenomenon which existed before the pandemic, this excess money created some manias in the markets, such as the crypto craze, the meme stock crowding, and the IPO and SPAC rush. Fortunately, these excesses remained somewhat contained and episodic, and much of the speculative air has since come out of these bubbles and they were not sufficient to cause a recession, as the strong consumer emerging from the pandemic continued to support the economy. Hence, the necessary (and perhaps also sufficient) condition for a recession remains a decline in consumer demand.

Source: FRED

To summarise, I highlighted some of the unique features of the COVID crisis – mainly its brevity and the unprecedented policy response – and I argued why the pandemic did not amount to a reset of the economic cycle. The recovery from the pandemic led to unusually high levels of spending and investment, which now look unsustainable given the normalisation of savings, the high inflation, and the weak consumer sentiment. However, do not expect any of these to cause an immediate recession on their own. Almost by definition, a recession is triggered by a sudden and unexpected event – such as the Iranian Revolution and oil shock of 1981-1982 or the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. One can only speculate on what the catalyst could be this time – an escalation of the war in Ukraine and oil reaching $200 per barrel, a recession in China, a more virulent COVID variant, or something else entirely. Ultimately, all such speculations are unfounded and should not form the basis of any investment thesis. Rather, I believe that the excessive consumer demand on its own should prompt prudent and defensive positioning, without necessarily selling out of risk assets. Below I explain how I would do this.

Investing In An Uncertain Consumer Demand Environment

Note: Due to length constraints, the following recommendations focus on large-cap equities from developed economies and the justifications offered are brief. The comments on sectoral allocations should be understood as an encouragement to be overweight or very selective in specific sectors, rather than to buy or sell everything in these sectors indiscriminately.

For long-term investors – where to hide from a decline in consumer demand:

Avoid or sell if owned:

Consumer discretionary stocks, especially companies selling durable goods, which tend to be cyclical (cars, electronics, appliances, furnishing etc.), but also luxury companies (the latter mainly due to the high valuations).

Pure advisory investment banks and private equity companies and some asset management stocks.

Residential real estate (both physical and REITS).

Ignore or be very selective in:

Most (but not all) cyclical industries, particularly oil and gas, as well as mining. I would note that the low multiples for these stocks are misleading and reflect more a surge in earnings than they do cheap valuations (I plan to discuss this in more detail in my next post, titled “The Cyclical Value Trap”). As a long-term investor, I would avoid taking a view on pure-play energy producers such as Pioneer (NYSE: PXD), since this is a direct bet on oil prices, which is inherently speculative. I would also be neutral agribusiness companies, such as Bunge (NYSE: BG) or Archer-Daniels-Midlands (NYSE: ADM). The case for oil and gas supermajors like Exxon (NYSE: XOM) and miners with commodity trading operations like Glencore (LON: GLEN) is much more complex.

Media and Entertainment. Again, a mixed picture – I would probably buy Netflix (NASDAQ: NFLX) on the recent decline, while I would avoid Disney (NYSE: DIS), but it is unclear to me how consumer spending would shift when it comes to media consumption.

Instead buy:

Consumer staples. This is too broad a sector to discuss in detail, but in food processing, focus on the higher end of the value chain, with preference towards strong brands with pricing power. In other words, choose companies like Danone (EPA: BN), Kellogg’s (NYSE: K), or Coca-Cola (NYSE: KO) over ingredient producers like Associated British Foods (LON: ABF) and McCormick (NYSE: MKC) or lower-end brands, like Conagra (NYSE: CAG), whose margins may shrink more due to higher input costs. In cosmetics and personal care, do the opposite, preferring mid-level brands like Unilever (LON: UL) or Colgate-Palmolive (NYSE: CP) over premium brands such as L’Oréal (EPA: OR) or Estée Lauder (NYSE: EL), which also have premium valuations.

Pharmaceuticals. Again, one should be somewhat selective here, mainly on the valuation. Some names I like are Takeda (TYO: 4502 or NYSE: TAK for the ADR), Sanofi (EPA: SAN), Novartis (SWX: NOVN), Gilead (NASDAQ: GILD), and Glaxo-Smith-Kline (LON: GSK). However, I would avoid the COVID vaccine makers, Pfizer (NYSE: PFE) and Moderna (NASDAQ: MRNA); as in the case of cyclical companies, don’t be misled by their low multiples.

Defence. This is a sector I would be particularly overweight, as it relies exclusively on government spending and has no exposure to the end consumer. While the majority of these stocks are now higher due to the war in Ukraine, the mostly reasonable valuations and the nearly guaranteed long-term increase in defence spending warrants owning these stocks. In the US, I like most large defence contractors – Lockheed-Martin (NYSE: LMT), Raytheon Technologies (NYSE: RTX), Northrop Grumman (NYSE: NOC) and Huntington Ingalls (NYSE: HII), although I omit General Dynamics (NYSE: GD) due to its large private jets exposure (Gulfstream). In Europe, I particularly like Leonardo (BIT: LDO) in Italy, and Rolls-Royce (LON: RR) in the UK, although the latter only generates about a third of its revenue from defence. I also mentioned some of these companies in my previous post, “War Hedges”.

Utilities and infrastructure companies. Here, I refrain from specific suggestions, as I do not have first-hand experience owning companies in these industries. However, the general idea is that infrastructure projects, such as railways, power plants, and pipelines, have little exposure to the consumer in the near-term. In utilities, I would prefer the larger players, which are better able to hedge against swings in energy prices – think NextEra (NYSE: NEE) in the US or EDF (EPA: EDF) and SSE (LON: SSE) in Europe. Clean energy and nuclear may also be interesting, due to the renewed focus on energy security, although here one has to be extra selective with valuations.

Do have some exposure to:

Financials, preferring insurance over banks, and preferring universal banks over pure retail or investment banks. Here the list is long again, but I personally like Manulife (TSX: MFC) and Citigroup (NYSE: C).

Travel, leisure, and hospitality, which can benefit from the end of the pandemic, while still currently trading at depressed historical levels (particularly cruise lines, which trade at 2009 lows).

Some companies in cyclical industries which benefit from the onshoring theme and from government-subsidised spending. For instance, while I recommend selling chip designers like Nvidia or AMD due to demand cyclicality, I would consider buying semiconductor capital equipment (Semicap) companies such as KLA (NASDAQ: KLAC), Applied Materials (NASDAQ: AMAT), or Lam Research (NASDAQ: LRCX). Semicaps benefit from the strategic expansion in domestic chip production capacity by every major power, a process which should continue regardless of changes in consumer demand.

Structural growth companies. I could write an entire post just about these, but in essence, instead of buying the FAANGS, I would rather focus on innovative tech and biotech companies, especially since many of these names have sold off significantly since January. Personally, being a bit more conservative, I own what I like to call “boring tech” companies, such as Cisco (NASDAQ: CSCO) and Oracle (NASDAQ: ORCL).

Think internationally: I believe that Japanese equities are especially worth a look. While Japan has its own set of risks, including energy fragility (Japan imports 93% of its energy), and further depreciation of the yen against the dollar, Japan benefits from relative calm when it comes to monetary policy, and the weak JPY also presents an opportunity to buy Japanese stocks more cheaply. Besides Takeda, which I already mentioned, among Nikkei 225 constituents, I like Murata Manufacturing (TYO: 6981), Sumimoto Mitsui Financial Group (TYO: 8316), FANUC (6954), Canon (TYO: 7751), Mitsubishi Electric (TYO: 6503), Komatsu (TYO: 6301), Panasonic (TYO: 6752), and Otsuka (TYO: 4578).

If you managed to make it this far, the core idea is to favour defensives over cyclicals, with some nuances around valuation and the specific customer exposure.

For speculators – how to profit from a fall in consumer demand (while limiting risk):

To profit:

Short consumer discretionary companies that have benefitted from strong demand in 2021. Focus especially on stocks with high multiples, high growth priced in, and unrecognised cyclicality. Two well-known examples are Nvidia (NASDAQ: NVDA) and Tesla (NASDAQ: TSLA), which, while fast-growing, are perceived as structural growth companies, despite operating in inherently cyclical industries. If shorting these outright or even with put options seems too risky, consider long-short trades. For instance, something like long Intel (NASDAQ: INTC) vs. short Nvidia (delta neutral) should largely neutralise the sector exposure, while capitalising on the relative valuation (P/E Intel 11 vs. P/E Nvidia 72) and on the difference in beta (beta Intel 1.22 vs. beta Nvidia 1.66). Tesla is too idiosyncratic for relative trades, except maybe against Bitcoin :)

Long travel vs. short durable goods. Here the idea is to neutralise exposure to cyclicality, while betting on a reversion to trend of the spending imbalance between goods and services (see the PCE chart below). One could thus go long an airline, say United Airlines (NASDAQ: UAL), while shorting a goods retailer, say Dick’s Sporting Goods (NYSE: DKS). These are extreme examples, since United is down 50% since the start of the pandemic, while Dick’s is up 145%, but other pairs can be found.

To limit risk:

In commodities, prefer relative trades along the futures curve or across benchmarks instead of directional trades.

Moderate the bet on rising rates – especially on the long-end, as weaker demand and employment (remember the Fed’s dual mandate on inflation and employment) may reduce the number of distant rate hikes, while the short-end would continue to be driven by the Fed’s desire to combat inflation.

Source: FRED

Over time, goods became cheaper due to globalisation (cheaper offshore production), while services did not, causing the ratio of goods to services spending to decrease steadily (and for even more than the plotted range). While some speculate that we may be entering a period of de-globalisation, in the short-term, the reversion of this spike will dominate.

Congratulations on making it to the end!